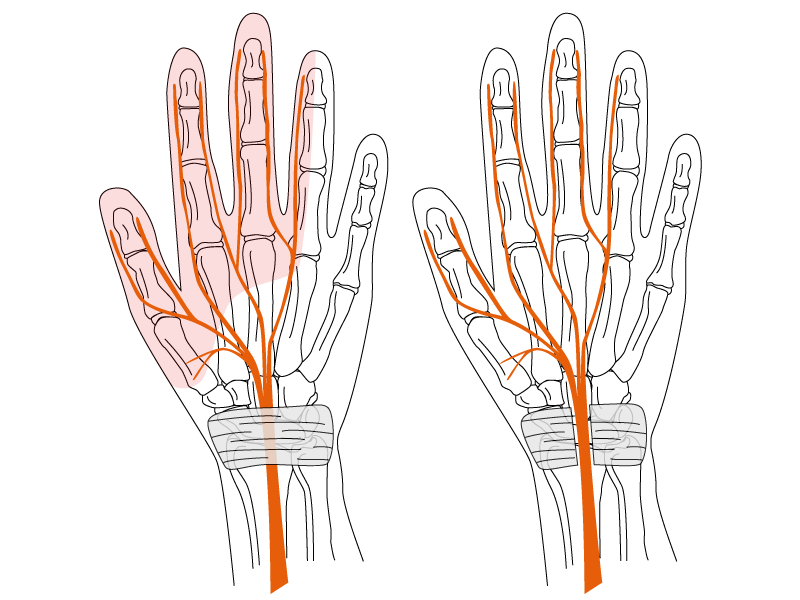

Carpal tunnel syndrome is one of the most common hand conditions, yet post-surgical assessment can be difficult, particularly in the medicolegal setting. Carpal tunnel release surgery is highly effective in relieving compression of the median nerve, however, a proportion of patients experience ongoing pain, scar sensitivity, or pillar discomfort despite satisfactory decompression. For lawyers and insurers, these cases can be challenging to interpret: surgical success does not always equate to full functional recovery, and residual symptoms may not align neatly with the measurable parameters defined in the impairment guidelines.

To use a clinical case as an example, a manual worker underwent staged bilateral decompressions with good resolution of classical carpal tunnel symptoms but later developed persistent palmar tenderness and pillar pain. Two assessors reached contrasting conclusions. One considered the symptoms non-specific, attributing them to inconsistent reporting and assigning 0% impairment. The other acknowledged the surgical success yet recognised symptomatic scarring as a legitimate source of ongoing limitation, assigning a modest impairment. The disagreement centred on the application of the AMA Guides to post-carpal tunnel scenarios, subjective symptoms and the absence of post-operative nerve conduction studies. Without such studies, the Guide defaults to 0% impairment, but this does not exclude assessment of scarring or disfigurement under separate provisions.

When such matters proceed to litigation, much can hinge on the claimant’s reported symptom profile and whether those symptoms are clinically reasonable given the available evidence. In some cases, there may be no overt objective features, yet a clear and plausible basis for ongoing symptoms exists, such as tender scarring or chronic pillar pain. The AMA Guides permit the use of clinical judgment in these circumstances, allowing the assessor to form an opinion on the balance of probabilities. The essential question becomes not whether the symptoms are measurable, but whether they are credible and consistent with the mechanism of injury and the surgical outcome.

For manual workers, even modest tenderness or sensitivity can have a disproportionate impact on daily function. Their hands are their tools and tasks often involve vibration, pressure, and repetitive load. A degree of discomfort that might be inconsequential for an office worker can meaningfully restrict a tradesperson’s capacity. The assessor’s role is to interpret these subtleties, quantifying impairment where possible, but also articulating how residual pain or hypersensitivity may limit function in practical terms. Such assessments demand not only familiarity with the Guides but also clinical experience and judgment. Objective data remain central, yet fairness depends on recognising that functional disability and measurable impairment are not always equivalent.

Ultimately, post-surgical carpal tunnel cases remind us that the purpose of medicolegal examination and impairment assessment is not merely to classify, but to clarify. The role of the assessor is to provide an evidence-based, clinically reasoned opinion that recognises both the objectivity of measurement and the legitimacy of well-founded subjective experience. When that balance is maintained, outcomes are fair, transparent, and consistent with both medical and legal principles.