It is inevitable that in the aftermath of cutaneous trauma and surgery that those injured will be left with scarring to some extent. While the goal of reconstructive surgery is to achieve stable, durable, and physically optimal wounds, the resultant scar carries with it a new set of symptoms and limitations. Recognition and documentation of these effects is the challenging role of the impairment assessor, and it is not all straightforward.

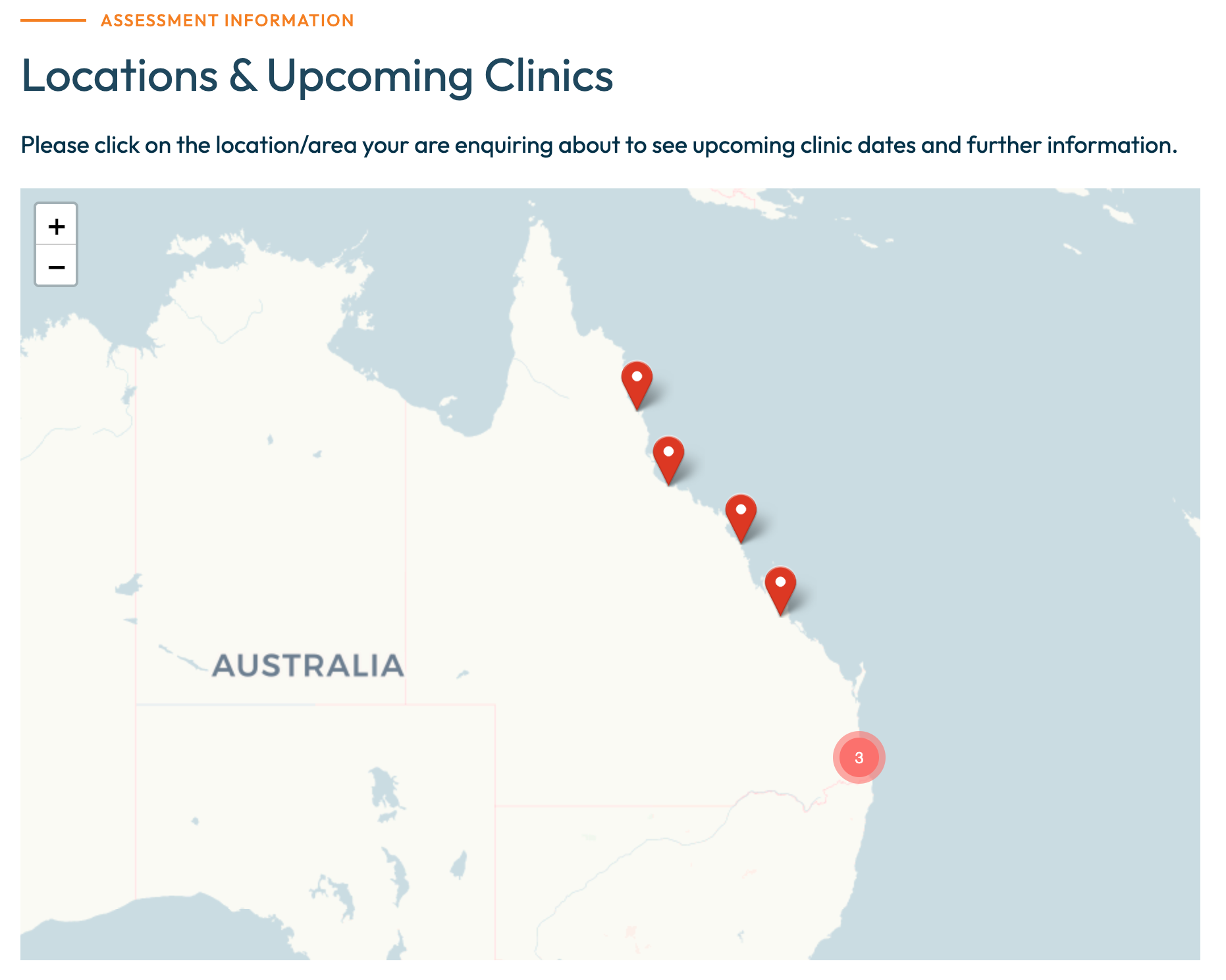

Major limb trauma and burn reconstruction frequently produce extensive scarring, and in a large state such as Queensland, regional and industrial areas unfortunately see an high number of these cases. In visiting centres such as Rockhampton, Mackay, and Townsville, I observe first-hand these complex injuries and navigate the technical and procedural challenges involved in examining for permanent impairment.

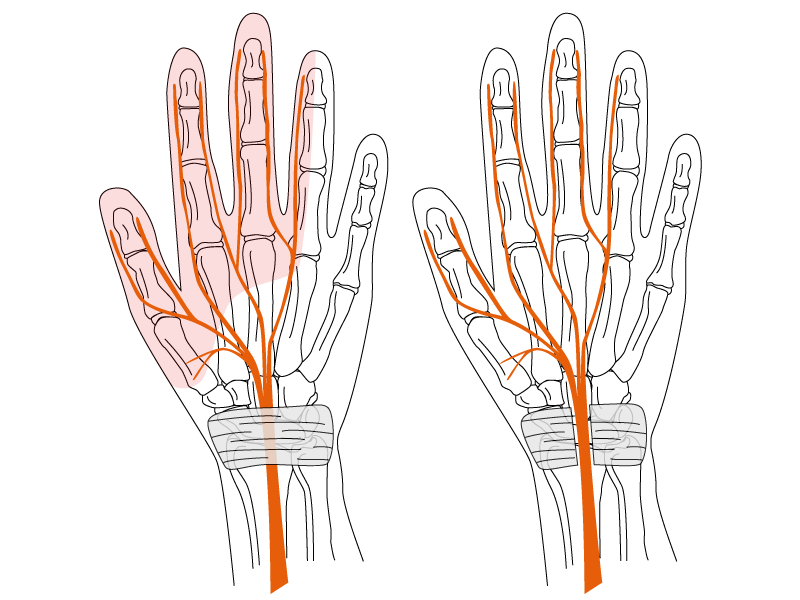

An important consideration in reconstructive surgery is that scars are not always confined to the site of the primary injury or pathology. When tissue flaps or grafts are used in reconstruction, there are donor-site scars, often remote from the area of reconstruction. These require assessment on their own merits for tenderness, adherence, and cosmetic prominence, and in some cases may be just as functionally significant as the primary scar. Consideration and respect for the implications of donor-site scarring and disfigurement are part of the mastery of reconstructive surgery. Similarly, the careful evaluation of all components and effects of post-traumatic scarring, both physical and psychosocial, forms part of the skill of permanent impairment assessment.

Under the AMA Guides and Guidelines to the Evaluation of Permanent Impairment (GEPI-2), the skin is regarded as a single organ. All non-facial scarring is therefore combined into a single overall impairment value, irrespective of the number or location of scars. While this approach provides consistency, it can sometimes dilute the cumulative effect of multiple operative and donor-site scars. The assessor must still describe each scar in detail, its site, size, contour, pigmentation, sensitivity, and texture and explain how these factors influence the overall functional outcome. Even then, the impairment figure may not always reflect the lived experience of the injured person, and the report should document the physical and cosmetic limitations transparently.

From a physical perspective, scar assessment should consider (amongst other things) site, size, adherence, contracture, fragility, and sensitivity. Limitation of joint motion, interference with workwear or protective garments, and the need for ongoing management such as compression garments or massage therapy are all relevant indicators of persistent impairment and disability. Where a scar restricts activities of daily living (whether through pain, fragility, or deformity) this should be reflected in both the descriptive findings and the impairment opinion. Fair assessment of scarring requires understanding its physical, functional, and social dimensions.

Appearance and function are closely linked, yet the psychological effect of visible disfigurement is often underestimated. A scar that is genuinely prominent, irregular, or unsightly can restrict social engagement and physical activity even in the absence of psychiatric illness. This is an effect of the scar itself, not a separate pathology or psychological disorder. Conversely, when a minor scar produces disproportionate distress or avoidance, that reaction may indeed reflect a distinct psychiatric condition. The distinction can be delicate and requires careful interpretation. This intersection between justifiably symptomatic physical scarring and inappropriate psychological response may be complex but it is essential to appreciate that a visibly disfiguring scar can legitimately alter confidence, social participation, and quality of life.

Scars may heal the wound, but they also shape the life that follows. It is the assessor’s responsibility is to ensure that both the physical scars and the individual behind them are properly recognised.